New New Delhi

July 3, 2020

A version of this essay appears in print in Log 51 (Winter 2021), published by Anyone Corporation.

Democracy in India is only top dressing on

an Indian soil which is essentially undemocratic.

– B.R. Ambedkar, chief architect of the Constitution of India, 1948

On September 2, 2019, the Central Public

Works Department of the Indian government published a seemingly innocuous bid online

and in Indian newspapers. It called for consultancy services from firms

specializing in architectural and engineering planning to spearhead the

redevelopment of Central Vista, a historic urban space at the heart of New

Delhi and the seat of several government buildings. The bid called for

“a new Master Plan . . . for the entire Central Vista area that represents the values and aspirations of a New India – Good Governance, Efficiency, Transparency, Accountability and Equity and is rooted in the Indian Culture and social milieu. The Master Plan shall entail concept, plan, detailed design and strategies development/redevelopment works, refurbishment works, demolition of existing buildings as well as related infrastructure and site development works. These new iconic structures shall be a legacy for 150 to 200 years at the very least.”1

The announcement was in some ways expected,

even by those who oppose the idea of changing the space. For years, the Indian government

has increasingly argued that several of the existing heritage buildings along the

vista are outdated and inadequate. Specifically, beyond complaints about maintenance

and improper structural conditions, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s administration

argues that more space will be needed when India’s Parliament expands following

the 2026 nationwide census.

What was unexpected was both the scale of

transformation suggested and the breakneck pace of the project deadlines: full

development of the vista’s public spaces by November 2020 (now extended to

2022), a new Parliament building by July 2022, a complete reorganization of

existing buildings and ministries by March 2024.2 The process of selection seemed equally rushed; just over a month later on

October 18, with only six firms submitting bids in total, the project was

awarded to Ahmedabad-based firm HCP Design, Planning and Management, with no

justification or proposal published. The project timeline only grew more

unrealistic: a draft master plan was expected within three weeks, drawings

sufficient to start construction in 26 weeks, and a complete master plan within

54 weeks.3 This

timeline is absurd considering the scale and importance of such a project.

Unsurprisingly, starting with the bid’s

publication the entire project has been heavily criticized for its lack of

transparency, rushed process, and obvious political motivation. Only one of the

six jury members has been publicly revealed.4 The

firm itself has released few details of their master plan beyond their initial

proposal. Many have criticized the estimated price tag of 20,000 crore rupees (approximately

2.675 billion dollars), especially in the wake of the ongoing coronavirus

pandemic. The project has been pushed forward even as the country struggles to

contain the number of cases. As MP and Congress Party spokesperson Abhishek

Singhvi said, “It shows the warped, distorted and completely absurd priorities

of this government. Bang in the middle of COVID-19, they are fast-tracking,

hot-footing the project.”5 Project

architect and director of HCP Design Bimal Patel is dismissive of most of these

concerns, saying that “sometimes, hesitation paralyses us. . . . People are so

worried about unthoughtful development that they want to see no change at all.”6 So,

with few means of establishing meaningful dialogue, a divide has opened between

those involved in the project and the citizens of Delhi.

The largest project of modern India, this

redevelopment will not only reinvent the vista but will likely become the model

of how urban public spaces in India will be designed. Without public discussion

about the proposed changes, the government charged forward and began

construction on January 15, 2021. More than its significance to the citizens of

Delhi, the Central Vista is the center of the world’s largest democracy. The

rushed, forced nature of the project is emblematic of how the Modi administration

looks to change the vista’s political image. Beyond the actual transformation,

there is far more at stake with this project and what it means for the future

of India’s democracy.

The Buildings Are Closing In

Understanding the implications behind this

project requires some history. The Central Vista was designed by English

architects Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker, as a part of their larger 1911 master

plan of New Delhi. The vista centers on the intersection of two promenades, the

Rajpath (King’s Way) and Janpath (Queen’s Way). The Rajpath is bookmarked on

one end by the Rashtrapati Bhavan (presidential palace) and on the other by the

India Gate. The Rashtrapati Bhavan is flanked on both sides by the Secretariat buildings,

with the Sansad Bhavan (parliament house) close by. In the master plan, land

closer to the India Gate was given to various princes, while several lots were

left open, intended as spaces for nature and for further development when

needed.7

![]()

Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker,

Central Vista, master plan of New Delhi, 1911. From Architectural Review 69, no.

410 (January 1931).

The master plan is one of the most

remarkable examples of a garden city design. Several geometric principles

underlie the morphology of the design; an equilateral triangle connects the

India Gate, Rashtrapati Bhavan, and Connaught Circus north of the vista, while

the site resolves into a hierarchy of triangles and hexagons that provide a

steady building rhythm moving from one street and lot to another. At the same

time, the space was highly privatized – the project was overtly colonial, intended

as a display of British rule and power and a departure from the dense

trade-based neighborhoods that typically composed Indian cities. Lutyens and

Baker drew inspiration from similar major axes and models of centralized power,

such as Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s Champs-Élysées in Paris and Pierre Charles L’Enfant’s

National Mall in Washington, DC. In his review of the new city and its

inauguration, Robert Byron wrote that the vista “is so arresting . . . that,

like a sovereign crowned and throned, it subordinates everything within view to

increase its own state, and stands not to be judged by, but to judge, its

attendants.”8

Postindependence and post-Partition, the

Delhi Development Act in 1957 and a subsequent new master plan in 1962 formally reclaimed the old administrative buildings for the new

government, demarcated most of the land around the vista as publicly

accessible, and negotiated for most of the princes’ estates to become public or

semipublic. The vista has served as the backdrop of several historic events and

national protests, including Gandhi’s funeral procession in 1948,

anti-cow-slaughter riots in 1966, farmers’ strikes from Mewat and Doab in 1988,

anti-rape protests in 2012, and most recently the anti–Citizenship Amendment

Act protests. In the words of architect Madhav Raman, “Without laying a brick

on this colonial space, over the past years of independence that we’ve had,

slowly but surely the people of this country have physically reclaimed this

space.”9

![]()

Anti–Citizenship Amendment Act protests, Central Vista, New Delhi,

January 2020. Photo courtesy IANS.

Despite every step toward the

democratization of the space, recent years have seen steps taken in the

opposite direction. Greater and greater restrictions on public gathering and

movement, all in the name of security, have been legally implemented, forcing

most gatherings away from the lawns of the vista toward smaller and more easily

contained urban spaces, such as Ramlila Ground.10 Informal occupants – street vendors, buskers, and hawkers – are policed more strictly

than ever before.11 Movement

in and around the vista has been curbed as the space has become commercialized,

and people passing through are subject to more security checks than ever.12 This erosion of public use reflects a crossroads in India: a future of vibrant

civic spaces or one of spaces governed by security.

This dialectic, architect Prem Chandavarkar

argues, should be front and center in any discussion of redevelopment, but “this

is far too important a question to be resolved solely within the confines of a

design competition. In fact, it is far too important to leave its resolution to

the deliberations of a small set of individuals, far too important to be

tackled within narrow sectors of expertise. This is a question for the nation

as a community.”13 Unfortunately, the new master plan begs to differ, continuing the trend toward security

and increased government presence. Under the justification of needing more room

for Parliament, the entire vista is being confined by additional government

buildings: the Secretariat is expanding into multiple buildings along the

Rajpath, replacing the current public-facing buildings with new structures that

will rehouse various ministries and administrative sectors that are presently spread across the city. The new, larger Parliament building sits

next to the existing Sansad Bhavan, taking over a public green space currently

occupied by temporary structures (or “hutments”) built during World War II that

house various administrative and military programs.

The expansion of the Secretariat buildings will

also remove several heritage buildings. No official master plan drawings have

been published, but from the proposal’s walk-through video, it appears that the

National Archives, the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, and Bikaner

House are among the many structures and spaces that will disappear.14 Many of these buildings are currently listed under different heritage statuses by the New Delhi Municipal Council – the

National Archives building, for instance, is Grade I protected, which gives legal

protection from any modification – yet they have been eerily erased without

explanation.15 This lack of information, as journalist Ashlin Mathew remarks, is dangerous:

“What the video doesn’t indicate speaks louder.”16 An entire history of architectural heritage is seemingly disregarded in one

sweep.

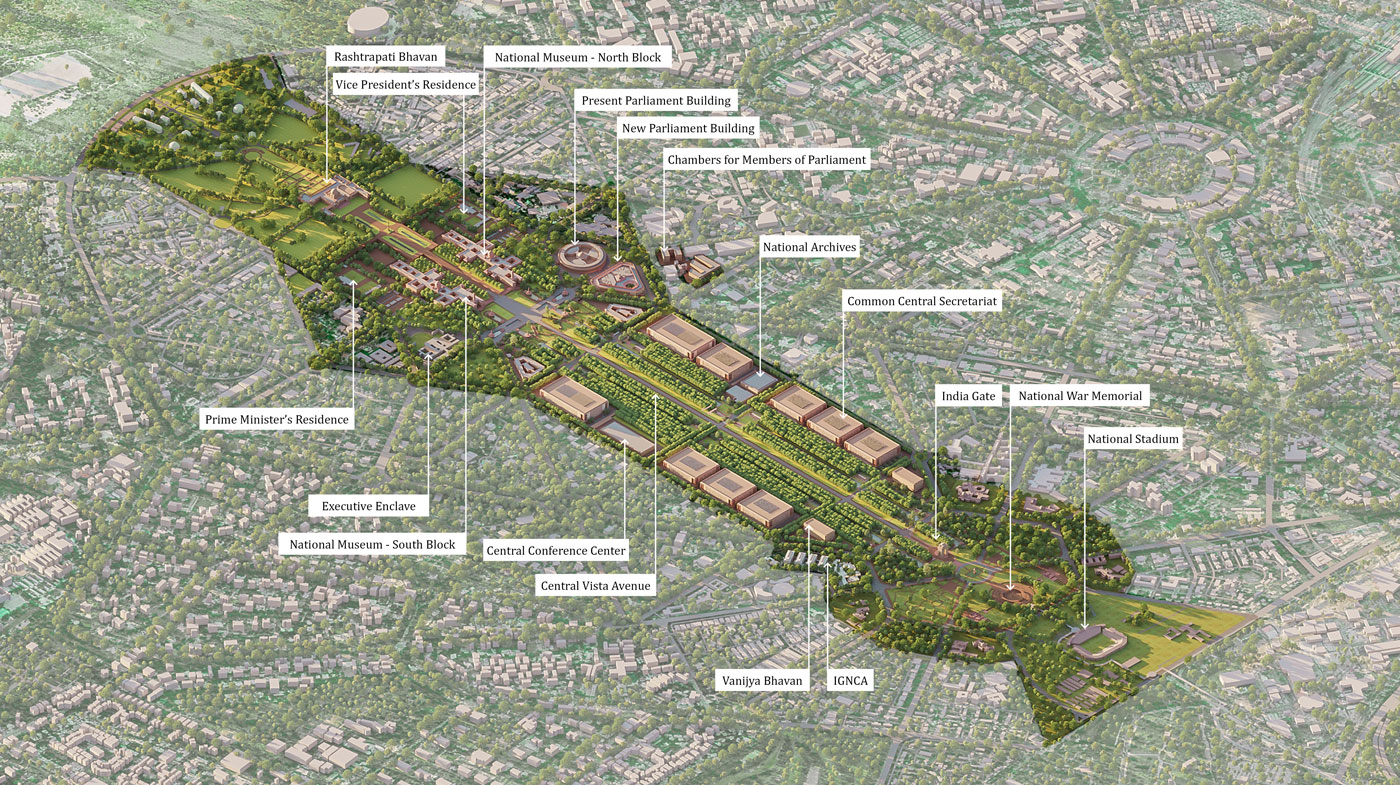

![]()

Labelled rendering of the new introduced structures.

From HCP Design’s project page.

Despite numerous petitions to the Supreme

Court challenging the project’s viability and violation of land-use laws – and

even a rebuke by the justices for the government’s “moving forward

aggressively” – the project was given approval by the court on January 5, 2021,

with all challenges dismissed.17 An investigation by the Heritage Conservation Committee, mandated by the

Supreme Court, led to the approval of the project just a week later, with no

acknowledgment of any potentially razed buildings, merely a vague declaration

that they had consulted building bylaws from 2016.18 In just a matter of weeks, with several state-approved institutional

thumbs-ups, the project was able to leapfrog the legitimate questions of its

impact on the vista.

The project architects themselves tell a different

story. In a lecture given at CEPT University – one of the rare occasions when the

project has been publicly discussed – Patel held a largely negative view of the

existing vista. He denounced the “inadequate facilities” of the existing

buildings, saw the vista as a collection of “disorderly and incoherent

architecture,” and argued that the crosshatch of public programs is

“ill-matched and incongruent.” His emphasis throughout the presentation was on

administration, calling the vista “an architectural icon for the Government of

India.”19 When pressed on the issue of disrespecting heritage, Patel was dismissive, retorting

“You find me one building where I have not been respectful.”20 His consistent redirection toward the need for new buildings avoids any

engagement on issues of public access, heritage, or transparency. With few

avenues to properly review the project as it is pushed through to completion,

the vista transformation now seems inevitable.

An Exercise in Power

There are broader implications to the

project, as architect A. Srivathsan writes: “Criticising the project only

because it overlooks the heritage value, though valid, is thin gruel. . . . The

problem hence is not entirely about its remaking. It lies in the answer to the

question: what purpose does it serve?”21 Beyond

the changes Delhi will experience, the very process speaks to larger questions

of how future public projects in the country will be carried out and how much

political power the government can enforce through shaping spaces.

In Architecture, Power, and National Identity,

Lawrence J. Vale describes exclusion as an “exercise of power” in civic spaces.22 This

exclusion is baked into the entire process of design selection and project

actualization. Despite the guise of an open competition, the criteria for entering

were incredibly strict, requiring (among other things) firms to have an average

annual turnover of 20 crore rupees and to have already completed a 500-acre master

plan – criteria that “even the most established firms in India will find

difficult to match.”23 A

more democratic approach would have cast as wide a net as possible, akin to a

two-stage open competition, which was used for the Indira Gandhi National Centre

for the Arts in 1986 and the new National War Memorial in 2016. These

precedents not only resulted in far more entries and longer decision periods

but also show that the process is not incongruent with an Indian context.

The decision to instead work with HCP

Design – who has designed other projects for Modi, including the development of

the Kashi Vishwanath corridor in Varanasi and the Mumbai Port Trust – reeks of

favoritism. When questioned about accusations of being a “pet architect,” Patel

was characteristically glib, saying, “Perhaps I am a good architect.”24 Many

have inferred that the selection has more to do with shared ideologies and

principles between the two. For instance, several of Patel’s designs draw on

Hindu symbolism and geometry, which can be viewed as being in line with Modi’s

Hindu nationalist views. Politician Tikender Singh Panwar argues that “this is

part of a larger hegemonic Hindutva project, where religious symbols are the

premise for the design.”25

Indeed, there is a blatant political agenda

behind the redevelopment of the vista. While there is certainly room to debate

the need for new structures or even a complete redevelopment of the vista,

particularly when pragmatic issues of capacity are raised, the operative verb –debate – has been missing from this entire process. For one thing,

several alternate design solutions have already been proposed that would modify

the existing Parliament building interior to

accommodate more members.26 For another, few efforts have been made to properly audit the existing

buildings, with even Patel admitting that there is little to no proper

documentation of these structures.27 The very nature of how or whether the Indian Parliament should expand has also

been questioned.28 The rush to finish the new Parliament building by 2022 – the 75th anniversary

of the nation – and the entire project by 2024 – the year of the next general

election – suggests Modi’s desire to directly associate his administration, its

nationalist philosophy, and this project. Little else can explain the urgency

with which the government has pushed forward. As architect Gautam Bhatia asks,

“Should a government with a limited tenure decide the future legacy of a

culture?”29 There are simply too many concerns glossed over; critics are labeled

contrarians who refuse to let India evolve, when the question is really howIndia should evolve. And the lack of discussion about the buildings that are

threatened erodes any trust that the government cares about these heritage

sites.

In Bhatia’s words, “A new strain of

thinking is now emerging, one that treats these old buildings like history

books, to be rewritten with fresh knowledge.”30 This top-down rewriting dismisses the residents and citizens as the primary

stakeholders of the space, dissolving personal experiences and histories in the

name of redefining India with a self-serving political symbol.

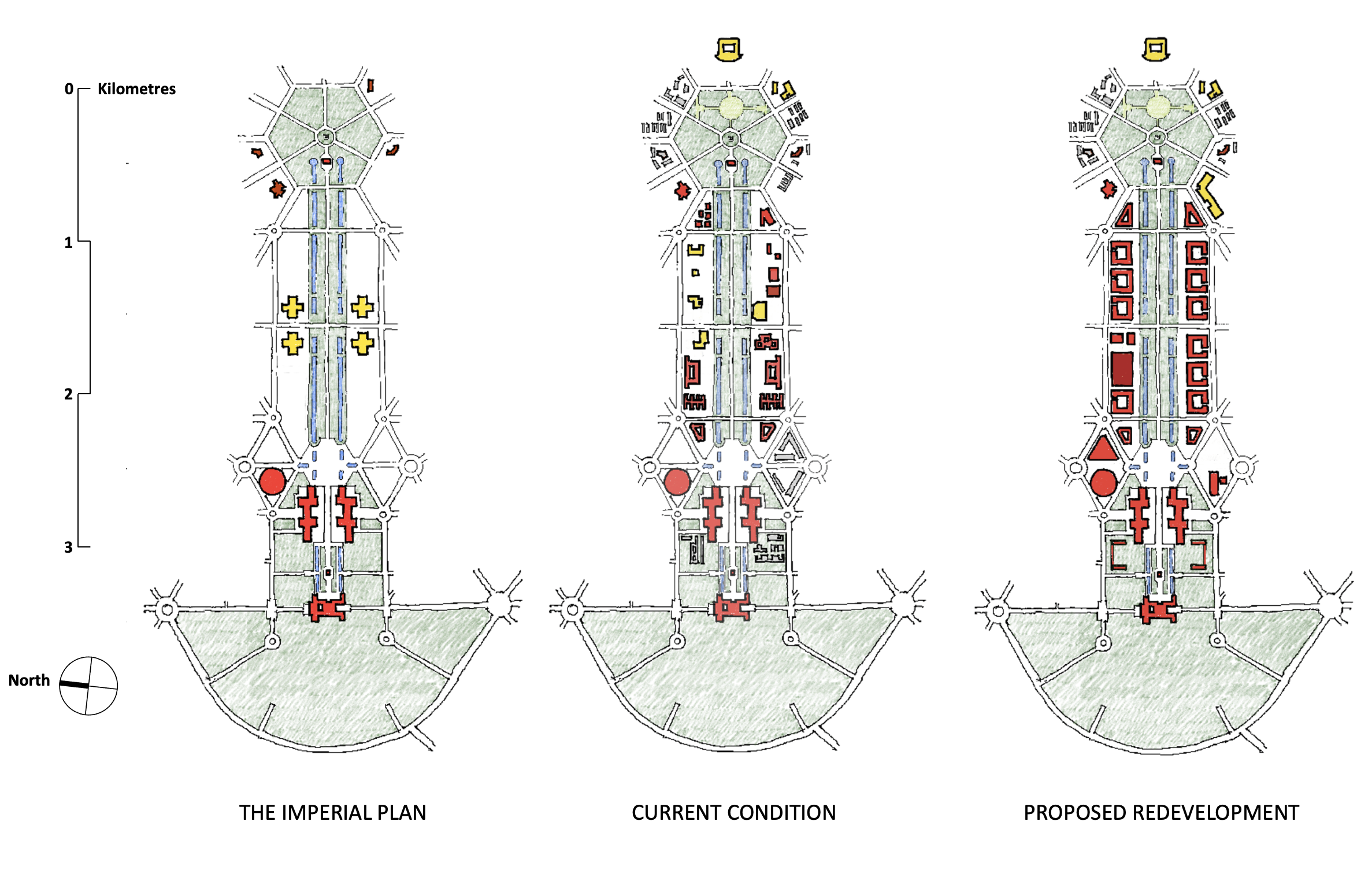

![]()

Prem Chandavarkar, plan diagrams of New Delhi’s original Central Vista,

its status as of 2020, and the proposed redevelopment based on presentations

by HCP Design, Planning and Management. Drawing courtesy the architect.

Stakes Swept Under

India is not alone in its state-imposed architectural

ambitions. The Trump administration signed an executive order in December 2020,

effectively mandating that federal architecture be built in a classical style.31 Similarly, in June 2020, China’s housing ministry outlined a “new era” for

China’s cities, limiting building heights and aiming to “highlight Chinese

characteristics.”32 Though India has not made any overt statement as such, it would seem that a new

India is already being reflected in its public projects, even as few understand

what this new India might entail and fewer still have any say in what it might be.

Is this project an exceptional case or just another step in a continuing

transformation that encroaches upon public space and imposes authority?33

Indian cities are in desperate need of

change as they adjust to incredibly rapid growth, and the country has very few

examples of successful urban planning. In large part, this has to do with an overly

centralized system of organization, with little local governance, resulting in

cities that fall apart and low citizen participation in planning. Among other

things, informal housing, local interventions, and community-led design are disregarded

in favor of grand gestures and master plans that usually do not work.34 Models of the city are boiled down to easily quantifiable data without proper

consideration, allowing sacrifices to be made. Journalist Alpana Kishore argues

that the government views open space as “a comfortably sacrificed element that

can easily withstand higher densities, traffic and built up space, and indeed

for ‘efficiency’s’ sake, should.”35 The

vista project was an opportunity for a strong example of planning: for rejecting

old practices and democratically building a space that could become a model for

future cities to follow. Instead, the government has eagerly dug shovels into

the existing vista and leapt headfirst into construction.

When Günter Behnisch designed an addition

to the parliament building in Bonn, Germany, in 1992, he spoke extensively on

the importance of architecture reflecting democracy in every essence of its

creation. According to historian Deborah Ascher Barnstone, “In the hundreds of

articles, essays, interviews, and other publications about the project,

Behnisch promotes the new Bundeshaus as a showcase for pluralism in the Federal

Republic, freedom of speech, participatory democracy and, above all, German

democracy at work.”36

The

same, unfortunately, will probably not be said of Delhi’s Central Vista.

1. Central Public Works Department, Government of India, Notice

Inviting Bids for Appointment of a Consultant, 04/CPM/RPZ/NIT/2019-20, September

5, 2019. “Notice Inviting Bids from National/International Design

& Planning Firms for Consultancy Services for comprehensive Architectural

& Engineering planning for the ‘Development/Redevelopment of Parliament

Building, Common Central Secretariat and Central Vista at New Delhi.’”

2. Ibid. The November 2020 deadline for the vista’s public spaces was pushed to July 2022, due to both the COVID-19 pandemic and delays in receiving construction permission from the Supreme Court.

3. See Prem Chandavarkar, in “Urban Design Politics, The proposed redevelopment of the Central Vista in New Delhi” (presentation, Bangalore International Centre, Bangalore, January 7, 2020), 2:09:52.

4. The jury was led by P.S.N. Rao, director of the School of Planning and Architecture Delhi; the other five members have not been identified. See Press Trust of India, “Centre appoints Ahmedabad-based consultant for makeover of Lutyens’ Delhi,” Economic Times, October 25, 2019.

5. In addition to this statement, Singhvi called the project a “hobby horse,” and added that “a more horrible attack on the heart and psyche of Delhi cannot be imagined.” “Central Vista project shows govt.’s warped priorities: Congress,” Hindu, May 2, 2020.

6. Indian Express, “Idea Exchange with Bimal Patel, Director, HCP Design,” January 11, 2020, 34:49.

7. For more information on Lutyens’s Delhi, see Andreas Volwahsen, Imperial Delhi: The British Capital of the Indian Empire (New York: Prestel, 2002).

8. Robert Byron, “New Delhi,” Architectural Review 69, no. 410 (January 1931): 6.

9. Madhav Raman, in “Urban Design Politics.”

10. New guidelines by the Delhi Police in 2018, for instance, implemented a limit on the number of protesters allowed and broad restrictions on how protests could be undertaken. See Delhi Police, Standing Order No. 10/2018: Guidelines for Organizing Protests or Demonstrations at or near Central Vista, Including Jantar Mantar and Boat Club, 2018.

11. See Prem Chandavarkar, “The State of a Nation Seen Through an Urban Design Competition,” Platform, December 12, 2019.

12. Urban planner and civil servant M.N. Buch described these measures as producing streets “suffering from almost terminal arteriosclerosis.” M.N. Buch, “Lutyens’ New Delhi – yesterday, today and tomorrow,” India International Centre Quarterly 30, no. 2 (Monsoon 2003): 33.

13. Chandavarkar, “The State of a Nation.”

14. The staggering list of other removed buildings includes Jawahar Bhawan, the Vice President’s residence, Hyderabad House, Baroda House, Jaipur House, Krishi Bhawan, Viavan Bhawan, Nirman Bhawan, Shashtri Bhawan, Jamnagar House, ASI Headquarters, Jawaharlal Nehru Bhawan, the National Museum, the Ministry of Tourism, Udyog Bhawan, and Princess Park. See A. Srivathsan, “BJP’s bid to rebuild Delhi’s Central Vista shows how keen it is to put its stamp even on built history,” Hindu, October 11, 2019; see also Ashlin Mathew, “Modi’s Central Vista plan: The emperor’s new residence and a vanity project!,” National Herald, November 4, 2019.

15. Although urban development minister Hardeep Singh Puri publicly assured that no listed heritage buildings will be touched without extensive permissions granted, he did not comment on how this would impact the extensive removals implied by the proposal nor give any indication as to which buildings would eventually need to be demolished. See Mohua Chatterjee, “Heritage buildings, precincts in the Central Vista region will be protected, Centre tells Parliament,” Times of India, February 4, 2021.

16. Mathew.

17. See Scroll Staff, “SC approves Central Vista redevelopment project in a majority verdict,” Scroll.in, January 5, 2021. Judicial affirmation should not be conflated with an assumed appropriateness of the project; see The Hindu Editorial, “Building by accord: On Central Vista,” Hindu, January 7, 2021.

18. The Heritage Conservation Committee approved the project on January 11. See Press Trust of India, “Heritage Conservation Committee approves construction of new parliament building,” Economic Times, January 11, 2021.

19. Bimal Patel, “Transforming Central Vista, New Delhi” (presentation, CEPT University, Ahmedabad, January 24, 2020), 2:41:09.

20. “Idea Exchange with Bimal Patel.”

21. Srivathsan.

22. Lawrence J. Vale, Architecture, Power, and National Identity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), 8.

23. Shiny Varghese, “Delhi: Architecture firms feel left out, cite issues with project criteria,” Indian Express, September 13, 2019.

24. “Idea Exchange with Bimal Patel.”

25. Tikender Singh Panwar, “Why the Central Vista Redesign Project is on Shaky Ground Itself,” NewsClick, April 22, 2020.

26. Madhav Raman, for instance, describes how simply removing two of the four main staircases into the chamber would give more than enough space for the desired number of MPs. He specifically notes that he does not endorse this as a solution per se, but that there is no discourse that would allow these counterproposals to happen. See Raman, in “Urban Design Politics.”

27. Patel.

28. See Milan Vaishnav and Jamie Hintson, “India’s Emerging Crisis of Representation,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, March 14, 2019.

29. Gautam Bhatia, “Who needs Lutyens?,” India Today, November 15, 2019.

30. Ibid.

31. See Exec. Order No. 13,967, 85 Fed. Reg. 83739 (Dec. 23, 2020).

32. See Oscar Holland, “No taller than 500M, no plagiarism: China signals ‘new era’ for architecture,” CNN, June 6, 2020.

33. As Amritha Ballal similarly asks in “Urban Design Politics.”

34. See Ananya Roy, “Why India Cannot Plan Its Cities: Informality, Insurgence, and the Idiom of Urbanization,” Planning Theory 8, no. 1 (2009): 76–87.

35. Alpana Kishore, “Government first, citizen last: Delhi Central Vista plan turns democracy on its head,” NewsLaundry, February 10, 2020. Emphasis original.

36. Deborah Ascher Barnstone, The Transparent State: Architecture and politics in postwar Germany (Routledge: New York, 2005), 138.

2. Ibid. The November 2020 deadline for the vista’s public spaces was pushed to July 2022, due to both the COVID-19 pandemic and delays in receiving construction permission from the Supreme Court.

3. See Prem Chandavarkar, in “Urban Design Politics, The proposed redevelopment of the Central Vista in New Delhi” (presentation, Bangalore International Centre, Bangalore, January 7, 2020), 2:09:52.

4. The jury was led by P.S.N. Rao, director of the School of Planning and Architecture Delhi; the other five members have not been identified. See Press Trust of India, “Centre appoints Ahmedabad-based consultant for makeover of Lutyens’ Delhi,” Economic Times, October 25, 2019.

5. In addition to this statement, Singhvi called the project a “hobby horse,” and added that “a more horrible attack on the heart and psyche of Delhi cannot be imagined.” “Central Vista project shows govt.’s warped priorities: Congress,” Hindu, May 2, 2020.

6. Indian Express, “Idea Exchange with Bimal Patel, Director, HCP Design,” January 11, 2020, 34:49.

7. For more information on Lutyens’s Delhi, see Andreas Volwahsen, Imperial Delhi: The British Capital of the Indian Empire (New York: Prestel, 2002).

8. Robert Byron, “New Delhi,” Architectural Review 69, no. 410 (January 1931): 6.

9. Madhav Raman, in “Urban Design Politics.”

10. New guidelines by the Delhi Police in 2018, for instance, implemented a limit on the number of protesters allowed and broad restrictions on how protests could be undertaken. See Delhi Police, Standing Order No. 10/2018: Guidelines for Organizing Protests or Demonstrations at or near Central Vista, Including Jantar Mantar and Boat Club, 2018.

11. See Prem Chandavarkar, “The State of a Nation Seen Through an Urban Design Competition,” Platform, December 12, 2019.

12. Urban planner and civil servant M.N. Buch described these measures as producing streets “suffering from almost terminal arteriosclerosis.” M.N. Buch, “Lutyens’ New Delhi – yesterday, today and tomorrow,” India International Centre Quarterly 30, no. 2 (Monsoon 2003): 33.

13. Chandavarkar, “The State of a Nation.”

14. The staggering list of other removed buildings includes Jawahar Bhawan, the Vice President’s residence, Hyderabad House, Baroda House, Jaipur House, Krishi Bhawan, Viavan Bhawan, Nirman Bhawan, Shashtri Bhawan, Jamnagar House, ASI Headquarters, Jawaharlal Nehru Bhawan, the National Museum, the Ministry of Tourism, Udyog Bhawan, and Princess Park. See A. Srivathsan, “BJP’s bid to rebuild Delhi’s Central Vista shows how keen it is to put its stamp even on built history,” Hindu, October 11, 2019; see also Ashlin Mathew, “Modi’s Central Vista plan: The emperor’s new residence and a vanity project!,” National Herald, November 4, 2019.

15. Although urban development minister Hardeep Singh Puri publicly assured that no listed heritage buildings will be touched without extensive permissions granted, he did not comment on how this would impact the extensive removals implied by the proposal nor give any indication as to which buildings would eventually need to be demolished. See Mohua Chatterjee, “Heritage buildings, precincts in the Central Vista region will be protected, Centre tells Parliament,” Times of India, February 4, 2021.

16. Mathew.

17. See Scroll Staff, “SC approves Central Vista redevelopment project in a majority verdict,” Scroll.in, January 5, 2021. Judicial affirmation should not be conflated with an assumed appropriateness of the project; see The Hindu Editorial, “Building by accord: On Central Vista,” Hindu, January 7, 2021.

18. The Heritage Conservation Committee approved the project on January 11. See Press Trust of India, “Heritage Conservation Committee approves construction of new parliament building,” Economic Times, January 11, 2021.

19. Bimal Patel, “Transforming Central Vista, New Delhi” (presentation, CEPT University, Ahmedabad, January 24, 2020), 2:41:09.

20. “Idea Exchange with Bimal Patel.”

21. Srivathsan.

22. Lawrence J. Vale, Architecture, Power, and National Identity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), 8.

23. Shiny Varghese, “Delhi: Architecture firms feel left out, cite issues with project criteria,” Indian Express, September 13, 2019.

24. “Idea Exchange with Bimal Patel.”

25. Tikender Singh Panwar, “Why the Central Vista Redesign Project is on Shaky Ground Itself,” NewsClick, April 22, 2020.

26. Madhav Raman, for instance, describes how simply removing two of the four main staircases into the chamber would give more than enough space for the desired number of MPs. He specifically notes that he does not endorse this as a solution per se, but that there is no discourse that would allow these counterproposals to happen. See Raman, in “Urban Design Politics.”

27. Patel.

28. See Milan Vaishnav and Jamie Hintson, “India’s Emerging Crisis of Representation,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, March 14, 2019.

29. Gautam Bhatia, “Who needs Lutyens?,” India Today, November 15, 2019.

30. Ibid.

31. See Exec. Order No. 13,967, 85 Fed. Reg. 83739 (Dec. 23, 2020).

32. See Oscar Holland, “No taller than 500M, no plagiarism: China signals ‘new era’ for architecture,” CNN, June 6, 2020.

33. As Amritha Ballal similarly asks in “Urban Design Politics.”

34. See Ananya Roy, “Why India Cannot Plan Its Cities: Informality, Insurgence, and the Idiom of Urbanization,” Planning Theory 8, no. 1 (2009): 76–87.

35. Alpana Kishore, “Government first, citizen last: Delhi Central Vista plan turns democracy on its head,” NewsLaundry, February 10, 2020. Emphasis original.

36. Deborah Ascher Barnstone, The Transparent State: Architecture and politics in postwar Germany (Routledge: New York, 2005), 138.

New New Delhi

July 3, 2020

A version of this essay appears in print in Log 51 (Winter 2021), published by Anyone Corporation.

Aerial rendering of the new redeveloped Central Vista. From HCP Design’s project page.

Democracy in India is only top dressing on

an Indian soil which is essentially undemocratic.

– B.R. Ambedkar, chief architect of the Constitution of India, 1948

On September 2, 2019, the Central Public

Works Department of the Indian government published a seemingly innocuous bid online

and in Indian newspapers. It called for consultancy services from firms

specializing in architectural and engineering planning to spearhead the

redevelopment of Central Vista, a historic urban space at the heart of New

Delhi and the seat of several government buildings. The bid called for

a new Master Plan . . . for the entire Central Vista area that represents the values and aspirations of a New India – Good Governance, Efficiency, Transparency, Accountability and Equity and is rooted in the Indian Culture and social milieu. The Master Plan shall entail concept, plan, detailed design and strategies development/redevelopment works, refurbishment works, demolition of existing buildings as well as related infrastructure and site development works. These new iconic structures shall be a legacy for 150 to 200 years at the very least.1

The announcement was in some ways expected,

even by those who oppose the idea of changing the space. For years, the Indian government

has increasingly argued that several of the existing heritage buildings along the

vista are outdated and inadequate. Specifically, beyond complaints about maintenance

and improper structural conditions, Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s administration

argues that more space will be needed when India’s Parliament expands following

the 2026 nationwide census.

What was unexpected was both the scale of

transformation suggested and the breakneck pace of the project deadlines: full

development of the vista’s public spaces by November 2020 (now extended to

2022), a new Parliament building by July 2022, a complete reorganization of

existing buildings and ministries by March 2024.2 The process of selection seemed equally rushed; just over a month later on

October 18, with only six firms submitting bids in total, the project was

awarded to Ahmedabad-based firm HCP Design, Planning and Management, with no

justification or proposal published. The project timeline only grew more

unrealistic: a draft master plan was expected within three weeks, drawings

sufficient to start construction in 26 weeks, and a complete master plan within

54 weeks.3 This

timeline is absurd considering the scale and importance of such a project.

Unsurprisingly, starting with the bid’s

publication the entire project has been heavily criticized for its lack of

transparency, rushed process, and obvious political motivation. Only one of the

six jury members has been publicly revealed.4 The

firm itself has released few details of their master plan beyond their initial

proposal. Many have criticized the estimated price tag of 20,000 crore rupees (approximately

2.675 billion dollars), especially in the wake of the ongoing coronavirus

pandemic. The project has been pushed forward even as the country struggles to

contain the number of cases. As MP and Congress Party spokesperson Abhishek

Singhvi said, “It shows the warped, distorted and completely absurd priorities

of this government. Bang in the middle of COVID-19, they are fast-tracking,

hot-footing the project.”5 Project

architect and director of HCP Design Bimal Patel is dismissive of most of these

concerns, saying that “sometimes, hesitation paralyses us. . . . People are so

worried about unthoughtful development that they want to see no change at all.”6 So,

with few means of establishing meaningful dialogue, a divide has opened between

those involved in the project and the citizens of Delhi.

The largest project of modern India, this

redevelopment will not only reinvent the vista but will likely become the model

of how urban public spaces in India will be designed. Without public discussion

about the proposed changes, the government charged forward and began

construction on January 15, 2021. More than its significance to the citizens of

Delhi, the Central Vista is the center of the world’s largest democracy. The

rushed, forced nature of the project is emblematic of how the Modi administration

looks to change the vista’s political image. Beyond the actual transformation,

there is far more at stake with this project and what it means for the future

of India’s democracy.

The Buildings Are Closing In

Understanding the implications behind this

project requires some history. The Central Vista was designed by English

architects Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker, as a part of their larger 1911 master

plan of New Delhi. The vista centers on the intersection of two promenades, the

Rajpath (King’s Way) and Janpath (Queen’s Way). The Rajpath is bookmarked on

one end by the Rashtrapati Bhavan (presidential palace) and on the other by the

India Gate. The Rashtrapati Bhavan is flanked on both sides by the Secretariat buildings,

with the Sansad Bhavan (parliament house) close by. In the master plan, land

closer to the India Gate was given to various princes, while several lots were

left open, intended as spaces for nature and for further development when

needed.7

![]()

Edwin Lutyens and Herbert Baker,

Central Vista, master plan of New Delhi, 1911. From Architectural Review 69, no.

410 (January 1931).

The master plan is one of the most

remarkable examples of a garden city design. Several geometric principles

underlie the morphology of the design; an equilateral triangle connects the

India Gate, Rashtrapati Bhavan, and Connaught Circus north of the vista, while

the site resolves into a hierarchy of triangles and hexagons that provide a

steady building rhythm moving from one street and lot to another. At the same

time, the space was highly privatized – the project was overtly colonial, intended

as a display of British rule and power and a departure from the dense

trade-based neighborhoods that typically composed Indian cities. Lutyens and

Baker drew inspiration from similar major axes and models of centralized power,

such as Georges-Eugène Haussmann’s Champs-Élysées in Paris and Pierre Charles L’Enfant’s

National Mall in Washington, DC. In his review of the new city and its

inauguration, Robert Byron wrote that the vista “is so arresting . . . that,

like a sovereign crowned and throned, it subordinates everything within view to

increase its own state, and stands not to be judged by, but to judge, its

attendants.”8

Postindependence and post-Partition, the

Delhi Development Act in 1957 and a subsequent new master plan in 1962 formally reclaimed the old administrative buildings for the new

government, demarcated most of the land around the vista as publicly

accessible, and negotiated for most of the princes’ estates to become public or

semipublic. The vista has served as the backdrop of several historic events and

national protests, including Gandhi’s funeral procession in 1948,

anti-cow-slaughter riots in 1966, farmers’ strikes from Mewat and Doab in 1988,

anti-rape protests in 2012, and most recently the anti–Citizenship Amendment

Act protests. In the words of architect Madhav Raman, “Without laying a brick

on this colonial space, over the past years of independence that we’ve had,

slowly but surely the people of this country have physically reclaimed this

space.”9

![]()

Anti–Citizenship Amendment Act protests, Central Vista, New Delhi,

January 2020. Photo courtesy IANS.

Despite every step toward the

democratization of the space, recent years have seen steps taken in the

opposite direction. Greater and greater restrictions on public gathering and

movement, all in the name of security, have been legally implemented, forcing

most gatherings away from the lawns of the vista toward smaller and more easily

contained urban spaces, such as Ramlila Ground.10 Informal occupants – street vendors, buskers, and hawkers – are policed more strictly

than ever before.11 Movement

in and around the vista has been curbed as the space has become commercialized,

and people passing through are subject to more security checks than ever.12 This erosion of public use reflects a crossroads in India: a future of vibrant

civic spaces or one of spaces governed by security.

This dialectic, architect Prem Chandavarkar

argues, should be front and center in any discussion of redevelopment, but “this

is far too important a question to be resolved solely within the confines of a

design competition. In fact, it is far too important to leave its resolution to

the deliberations of a small set of individuals, far too important to be

tackled within narrow sectors of expertise. This is a question for the nation

as a community.”13 Unfortunately, the new master plan begs to differ, continuing the trend toward security

and increased government presence. Under the justification of needing more room

for Parliament, the entire vista is being confined by additional government

buildings: the Secretariat is expanding into multiple buildings along the

Rajpath, replacing the current public-facing buildings with new structures that

will rehouse various ministries and administrative sectors that are presently spread across the city. The new, larger Parliament building sits

next to the existing Sansad Bhavan, taking over a public green space currently

occupied by temporary structures (or “hutments”) built during World War II that

house various administrative and military programs.

The expansion of the Secretariat buildings will

also remove several heritage buildings. No official master plan drawings have

been published, but from the proposal’s walk-through video, it appears that the

National Archives, the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, and Bikaner

House are among the many structures and spaces that will disappear.14 Many of these buildings are currently listed under different heritage statuses by the New Delhi Municipal Council – the

National Archives building, for instance, is Grade I protected, which gives legal

protection from any modification – yet they have been eerily erased without

explanation.15 This lack of information, as journalist Ashlin Mathew remarks, is dangerous:

“What the video doesn’t indicate speaks louder.”16 An entire history of architectural heritage is seemingly disregarded in one

sweep.

![]()

Labelled rendering of the new introduced structures.

From HCP Design’s project page.

Despite numerous petitions to the Supreme

Court challenging the project’s viability and violation of land-use laws – and

even a rebuke by the justices for the government’s “moving forward

aggressively” – the project was given approval by the court on January 5, 2021,

with all challenges dismissed.17 An investigation by the Heritage Conservation Committee, mandated by the

Supreme Court, led to the approval of the project just a week later, with no

acknowledgment of any potentially razed buildings, merely a vague declaration

that they had consulted building bylaws from 2016.18 In just a matter of weeks, with several state-approved institutional

thumbs-ups, the project was able to leapfrog the legitimate questions of its

impact on the vista.

The project architects themselves tell a different

story. In a lecture given at CEPT University – one of the rare occasions when the

project has been publicly discussed – Patel held a largely negative view of the

existing vista. He denounced the “inadequate facilities” of the existing

buildings, saw the vista as a collection of “disorderly and incoherent

architecture,” and argued that the crosshatch of public programs is

“ill-matched and incongruent.” His emphasis throughout the presentation was on

administration, calling the vista “an architectural icon for the Government of

India.”19 When pressed on the issue of disrespecting heritage, Patel was dismissive, retorting

“You find me one building where I have not been respectful.”20 His consistent redirection toward the need for new buildings avoids any

engagement on issues of public access, heritage, or transparency. With few

avenues to properly review the project as it is pushed through to completion,

the vista transformation now seems inevitable.

An Exercise in Power

There are broader implications to the

project, as architect A. Srivathsan writes: “Criticising the project only

because it overlooks the heritage value, though valid, is thin gruel. . . . The

problem hence is not entirely about its remaking. It lies in the answer to the

question: what purpose does it serve?”21 Beyond

the changes Delhi will experience, the very process speaks to larger questions

of how future public projects in the country will be carried out and how much

political power the government can enforce through shaping spaces.

In Architecture, Power, and National Identity,

Lawrence J. Vale describes exclusion as an “exercise of power” in civic spaces.22 This

exclusion is baked into the entire process of design selection and project

actualization. Despite the guise of an open competition, the criteria for entering

were incredibly strict, requiring (among other things) firms to have an average

annual turnover of 20 crore rupees and to have already completed a 500-acre master

plan – criteria that “even the most established firms in India will find

difficult to match.”23 A

more democratic approach would have cast as wide a net as possible, akin to a

two-stage open competition, which was used for the Indira Gandhi National Centre

for the Arts in 1986 and the new National War Memorial in 2016. These

precedents not only resulted in far more entries and longer decision periods

but also show that the process is not incongruent with an Indian context.

The decision to instead work with HCP

Design – who has designed other projects for Modi, including the development of

the Kashi Vishwanath corridor in Varanasi and the Mumbai Port Trust – reeks of

favoritism. When questioned about accusations of being a “pet architect,” Patel

was characteristically glib, saying, “Perhaps I am a good architect.”24 Many

have inferred that the selection has more to do with shared ideologies and

principles between the two. For instance, several of Patel’s designs draw on

Hindu symbolism and geometry, which can be viewed as being in line with Modi’s

Hindu nationalist views. Politician Tikender Singh Panwar argues that “this is

part of a larger hegemonic Hindutva project, where religious symbols are the

premise for the design.”25

Indeed, there is a blatant political agenda

behind the redevelopment of the vista. While there is certainly room to debate

the need for new structures or even a complete redevelopment of the vista,

particularly when pragmatic issues of capacity are raised, the operative verb –debate – has been missing from this entire process. For one thing,

several alternate design solutions have already been proposed that would modify

the existing Parliament building interior to

accommodate more members.26 For another, few efforts have been made to properly audit the existing

buildings, with even Patel admitting that there is little to no proper

documentation of these structures.27 The very nature of how or whether the Indian Parliament should expand has also

been questioned.28 The rush to finish the new Parliament building by 2022 – the 75th anniversary

of the nation – and the entire project by 2024 – the year of the next general

election – suggests Modi’s desire to directly associate his administration, its

nationalist philosophy, and this project. Little else can explain the urgency

with which the government has pushed forward. As architect Gautam Bhatia asks,

“Should a government with a limited tenure decide the future legacy of a

culture?”29 There are simply too many concerns glossed over; critics are labeled

contrarians who refuse to let India evolve, when the question is really howIndia should evolve. And the lack of discussion about the buildings that are

threatened erodes any trust that the government cares about these heritage

sites.

In Bhatia’s words, “A new strain of

thinking is now emerging, one that treats these old buildings like history

books, to be rewritten with fresh knowledge.”30 This top-down rewriting dismisses the residents and citizens as the primary

stakeholders of the space, dissolving personal experiences and histories in the

name of redefining India with a self-serving political symbol.

![]()

Prem Chandavarkar, plan diagrams of New Delhi’s original Central Vista,

its status as of 2020, and the proposed redevelopment based on presentations

by HCP Design, Planning and Management. Drawing courtesy the architect.

Stakes Swept Under

India is not alone in its state-imposed architectural

ambitions. The Trump administration signed an executive order in December 2020,

effectively mandating that federal architecture be built in a classical style.31 Similarly, in June 2020, China’s housing ministry outlined a “new era” for

China’s cities, limiting building heights and aiming to “highlight Chinese

characteristics.”32 Though India has not made any overt statement as such, it would seem that a new

India is already being reflected in its public projects, even as few understand

what this new India might entail and fewer still have any say in what it might be.

Is this project an exceptional case or just another step in a continuing

transformation that encroaches upon public space and imposes authority?33

Indian cities are in desperate need of

change as they adjust to incredibly rapid growth, and the country has very few

examples of successful urban planning. In large part, this has to do with an overly

centralized system of organization, with little local governance, resulting in

cities that fall apart and low citizen participation in planning. Among other

things, informal housing, local interventions, and community-led design are disregarded

in favor of grand gestures and master plans that usually do not work.34 Models of the city are boiled down to easily quantifiable data without proper

consideration, allowing sacrifices to be made. Journalist Alpana Kishore argues

that the government views open space as “a comfortably sacrificed element that

can easily withstand higher densities, traffic and built up space, and indeed

for ‘efficiency’s’ sake, should.”35 The

vista project was an opportunity for a strong example of planning: for rejecting

old practices and democratically building a space that could become a model for

future cities to follow. Instead, the government has eagerly dug shovels into

the existing vista and leapt headfirst into construction.

When Günter Behnisch designed an addition

to the parliament building in Bonn, Germany, in 1992, he spoke extensively on

the importance of architecture reflecting democracy in every essence of its

creation. According to historian Deborah Ascher Barnstone, “In the hundreds of

articles, essays, interviews, and other publications about the project,

Behnisch promotes the new Bundeshaus as a showcase for pluralism in the Federal

Republic, freedom of speech, participatory democracy and, above all, German

democracy at work.”36

The

same, unfortunately, will probably not be said of Delhi’s Central Vista.

1. Central Public Works Department, Government of India, Notice

Inviting Bids for Appointment of a Consultant, 04/CPM/RPZ/NIT/2019-20, September

5, 2019. “Notice Inviting Bids from National/International Design

& Planning Firms for Consultancy Services for comprehensive Architectural

& Engineering planning for the ‘Development/Redevelopment of Parliament

Building, Common Central Secretariat and Central Vista at New Delhi.’”

2. Ibid. The November 2020 deadline for the vista’s public spaces was pushed to July 2022, due to both the COVID-19 pandemic and delays in receiving construction permission from the Supreme Court.

3. See Prem Chandavarkar, in “Urban Design Politics, The proposed redevelopment of the Central Vista in New Delhi” (presentation, Bangalore International Centre, Bangalore, January 7, 2020), 2:09:52.

4. The jury was led by P.S.N. Rao, director of the School of Planning and Architecture Delhi; the other five members have not been identified. See Press Trust of India, “Centre appoints Ahmedabad-based consultant for makeover of Lutyens’ Delhi,” Economic Times, October 25, 2019.

5. In addition to this statement, Singhvi called the project a “hobby horse,” and added that “a more horrible attack on the heart and psyche of Delhi cannot be imagined.” “Central Vista project shows govt.’s warped priorities: Congress,” Hindu, May 2, 2020.

6. Indian Express, “Idea Exchange with Bimal Patel, Director, HCP Design,”January 11, 2020, 34:49.

7. For more information on Lutyens’s Delhi, see Andreas Volwahsen, Imperial Delhi: The British Capital of the Indian Empire (New York: Prestel, 2002).

8. Robert Byron, “New Delhi,” Architectural Review 69, no. 410 (January 1931): 6.

9. Madhav Raman, in “Urban Design Politics.”

10. New guidelines by the Delhi Police in 2018, for instance, implemented a limit on the number of protesters allowed and broad restrictions on how protests could be undertaken. See Delhi Police, Standing Order No. 10/2018: Guidelines for Organizing Protests or Demonstrations at or near Central Vista, Including Jantar Mantar and Boat Club, 2018.

11. See Prem Chandavarkar, “The State of a Nation Seen Through an Urban Design Competition,” Platform, December 12, 2019.

12. Urban planner and civil servant M.N. Buch described these measures as producing streets “suffering from almost terminal arteriosclerosis.” M.N. Buch, “Lutyens’ New Delhi – yesterday, today and tomorrow,” India International Centre Quarterly 30, no. 2 (Monsoon 2003): 33.

13. Chandavarkar, “The State of a Nation.”

14. The staggering list of other removed buildings includes Jawahar Bhawan, the Vice President’s residence, Hyderabad House, Baroda House, Jaipur House, Krishi Bhawan, Viavan Bhawan, Nirman Bhawan, Shashtri Bhawan, Jamnagar House, ASI Headquarters, Jawaharlal Nehru Bhawan, the National Museum, the Ministry of Tourism, Udyog Bhawan, and Princess Park. See A. Srivathsan, “BJP’s bid to rebuild Delhi’s Central Vista shows how keen it is to put its stamp even on built history,” Hindu, October 11, 2019; see also Ashlin Mathew, “Modi’s Central Vista plan: The emperor’s new residence and a vanity project!,” National Herald, November 4, 2019.

15. Although urban development minister Hardeep Singh Puri publicly assured that no listed heritage buildings will be touched without extensive permissions granted, he did not comment on how this would impact the extensive removals implied by the proposal nor give any indication as to which buildings would eventually need to be demolished. See Mohua Chatterjee, “Heritage buildings, precincts in the Central Vista region will be protected, Centre tells Parliament,” Times of India, February 4, 2021.

16. Mathew.

17. See Scroll Staff, “SC approves Central Vista redevelopment project in a majority verdict,” Scroll.in, January 5, 2021. Judicial affirmation should not be conflated with an assumed appropriateness of the project; see The Hindu Editorial, “Building by accord: On Central Vista,” Hindu, January 7, 2021.

18. The Heritage Conservation Committee approved the project on January 11. See Press Trust of India, “Heritage Conservation Committee approves construction of new parliament building,” Economic Times, January 11, 2021.

19. Bimal Patel, “Transforming Central Vista, New Delhi”(presentation, CEPT University, Ahmedabad, January 24, 2020), 2:41:09.

20. “Idea Exchange with Bimal Patel.”

21. Srivathsan.

22. Lawrence J. Vale, Architecture, Power, and National Identity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), 8.

23. Shiny Varghese, “Delhi: Architecture firms feel left out, cite issues with project criteria,” Indian Express, September 13, 2019.

24. “Idea Exchange with Bimal Patel.”

25. Tikender Singh Panwar, “Why the Central Vista Redesign Project is on Shaky Ground Itself,” NewsClick, April 22, 2020.

26. Madhav Raman, for instance, describes how simply removing two of the four main staircases into the chamber would give more than enough space for the desired number of MPs. He specifically notes that he does not endorse this as a solution per se, but that there is no discourse that would allow these counterproposals to happen. See Raman, in “Urban Design Politics.”

27. Patel.

28. See Milan Vaishnav and Jamie Hintson, “India’s Emerging Crisis of Representation,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, March 14, 2019.

29. Gautam Bhatia, “Who needs Lutyens?,” India Today, November 15, 2019.

30. Ibid.

31. See Exec. Order No. 13,967, 85 Fed. Reg. 83739 (Dec. 23, 2020).

32. See Oscar Holland, “No taller than 500M, no plagiarism: China signals ‘new era’ for architecture,” CNN, June 6, 2020.

33. As Amritha Ballal similarly asks in “Urban Design Politics.”

34. See Ananya Roy, “Why India Cannot Plan Its Cities: Informality, Insurgence, and the Idiom of Urbanization,” Planning Theory 8, no. 1 (2009): 76–87.

35. Alpana Kishore, “Government first, citizen last: Delhi Central Vista plan turns democracy on its head,” NewsLaundry, February 10, 2020. Emphasis original.

36. Deborah Ascher Barnstone, The Transparent State: Architecture and politics in postwar Germany (Routledge: New York, 2005), 138.

2. Ibid. The November 2020 deadline for the vista’s public spaces was pushed to July 2022, due to both the COVID-19 pandemic and delays in receiving construction permission from the Supreme Court.

3. See Prem Chandavarkar, in “Urban Design Politics, The proposed redevelopment of the Central Vista in New Delhi” (presentation, Bangalore International Centre, Bangalore, January 7, 2020), 2:09:52.

4. The jury was led by P.S.N. Rao, director of the School of Planning and Architecture Delhi; the other five members have not been identified. See Press Trust of India, “Centre appoints Ahmedabad-based consultant for makeover of Lutyens’ Delhi,” Economic Times, October 25, 2019.

5. In addition to this statement, Singhvi called the project a “hobby horse,” and added that “a more horrible attack on the heart and psyche of Delhi cannot be imagined.” “Central Vista project shows govt.’s warped priorities: Congress,” Hindu, May 2, 2020.

6. Indian Express, “Idea Exchange with Bimal Patel, Director, HCP Design,”January 11, 2020, 34:49.

7. For more information on Lutyens’s Delhi, see Andreas Volwahsen, Imperial Delhi: The British Capital of the Indian Empire (New York: Prestel, 2002).

8. Robert Byron, “New Delhi,” Architectural Review 69, no. 410 (January 1931): 6.

9. Madhav Raman, in “Urban Design Politics.”

10. New guidelines by the Delhi Police in 2018, for instance, implemented a limit on the number of protesters allowed and broad restrictions on how protests could be undertaken. See Delhi Police, Standing Order No. 10/2018: Guidelines for Organizing Protests or Demonstrations at or near Central Vista, Including Jantar Mantar and Boat Club, 2018.

11. See Prem Chandavarkar, “The State of a Nation Seen Through an Urban Design Competition,” Platform, December 12, 2019.

12. Urban planner and civil servant M.N. Buch described these measures as producing streets “suffering from almost terminal arteriosclerosis.” M.N. Buch, “Lutyens’ New Delhi – yesterday, today and tomorrow,” India International Centre Quarterly 30, no. 2 (Monsoon 2003): 33.

13. Chandavarkar, “The State of a Nation.”

14. The staggering list of other removed buildings includes Jawahar Bhawan, the Vice President’s residence, Hyderabad House, Baroda House, Jaipur House, Krishi Bhawan, Viavan Bhawan, Nirman Bhawan, Shashtri Bhawan, Jamnagar House, ASI Headquarters, Jawaharlal Nehru Bhawan, the National Museum, the Ministry of Tourism, Udyog Bhawan, and Princess Park. See A. Srivathsan, “BJP’s bid to rebuild Delhi’s Central Vista shows how keen it is to put its stamp even on built history,” Hindu, October 11, 2019; see also Ashlin Mathew, “Modi’s Central Vista plan: The emperor’s new residence and a vanity project!,” National Herald, November 4, 2019.

15. Although urban development minister Hardeep Singh Puri publicly assured that no listed heritage buildings will be touched without extensive permissions granted, he did not comment on how this would impact the extensive removals implied by the proposal nor give any indication as to which buildings would eventually need to be demolished. See Mohua Chatterjee, “Heritage buildings, precincts in the Central Vista region will be protected, Centre tells Parliament,” Times of India, February 4, 2021.

16. Mathew.

17. See Scroll Staff, “SC approves Central Vista redevelopment project in a majority verdict,” Scroll.in, January 5, 2021. Judicial affirmation should not be conflated with an assumed appropriateness of the project; see The Hindu Editorial, “Building by accord: On Central Vista,” Hindu, January 7, 2021.

18. The Heritage Conservation Committee approved the project on January 11. See Press Trust of India, “Heritage Conservation Committee approves construction of new parliament building,” Economic Times, January 11, 2021.

19. Bimal Patel, “Transforming Central Vista, New Delhi”(presentation, CEPT University, Ahmedabad, January 24, 2020), 2:41:09.

20. “Idea Exchange with Bimal Patel.”

21. Srivathsan.

22. Lawrence J. Vale, Architecture, Power, and National Identity (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), 8.

23. Shiny Varghese, “Delhi: Architecture firms feel left out, cite issues with project criteria,” Indian Express, September 13, 2019.

24. “Idea Exchange with Bimal Patel.”

25. Tikender Singh Panwar, “Why the Central Vista Redesign Project is on Shaky Ground Itself,” NewsClick, April 22, 2020.

26. Madhav Raman, for instance, describes how simply removing two of the four main staircases into the chamber would give more than enough space for the desired number of MPs. He specifically notes that he does not endorse this as a solution per se, but that there is no discourse that would allow these counterproposals to happen. See Raman, in “Urban Design Politics.”

27. Patel.

28. See Milan Vaishnav and Jamie Hintson, “India’s Emerging Crisis of Representation,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, March 14, 2019.

29. Gautam Bhatia, “Who needs Lutyens?,” India Today, November 15, 2019.

30. Ibid.

31. See Exec. Order No. 13,967, 85 Fed. Reg. 83739 (Dec. 23, 2020).

32. See Oscar Holland, “No taller than 500M, no plagiarism: China signals ‘new era’ for architecture,” CNN, June 6, 2020.

33. As Amritha Ballal similarly asks in “Urban Design Politics.”

34. See Ananya Roy, “Why India Cannot Plan Its Cities: Informality, Insurgence, and the Idiom of Urbanization,” Planning Theory 8, no. 1 (2009): 76–87.

35. Alpana Kishore, “Government first, citizen last: Delhi Central Vista plan turns democracy on its head,” NewsLaundry, February 10, 2020. Emphasis original.

36. Deborah Ascher Barnstone, The Transparent State: Architecture and politics in postwar Germany (Routledge: New York, 2005), 138.